Over recent years, my travels across India ignited my fascination with how tattoos hold cultural significance among different Indian communities. In many areas, tattoos serve as symbols tied to tribal customs. One community that particularly intrigued me was the Ramnami of Central India. When I shared this with a friend, she too showed interest in delving deeper into this culture. We eventually connected with a community member who graciously allowed us to visit his village, even inviting us to stay with his family. We happily arranged our visit.

Getting there

We initially flew from Bangalore to Raipur. From there, we caught a local bus to the GPM district. Subsequently, we explored GPM by taxi, which dropped us off at Chandlidih, the Ramnami village. It was raining heavily as we navigated the damaged, flooded roads and finally arrived at the location indicated by Google Maps. We carried our backpacks while crossing a small reservoir wall built over a stream swollen by the monsoon. On the other side was our host’s house. By the time we reached the front yard of the Ramnami family’s modest home, we were covered in mud from puddles stretching from the parking lot to the house.

Welcome to the Ramnami home

Our host welcomed us upon arrival and directed us to the guest room to drop off our luggage. The room, an extension of the main house, was built with cob and wood, offering basic amenities such as two beds for resting and a light bulb for illumination at night. We relied on mobile internet throughout our stay. According to tradition, anyone visiting from outside must bathe and cleanse themselves before entering a Ramnami home. The next experience was something my friend and I will both remember for a long time: the bathroom!

It was a simple enclosure with two and a half walls and a roof. Half of the third wall was intentionally built to shoulder height, making it easy to bring in water from outside either with buckets or through a gravity pipe connected to a nearby perennial stream that filled a concrete tank inside the bathroom. The fourth side was left open for easy access, featuring a modest saree stitched into a sliding blind that could be moved to open or close. There was no running water; hot water had to be fetched from an outdoor firewood oven, or one had to make do with the chilly water stored in the tank inside. Our city dwelling bodies were used to a sturdy lockable door for bathing with unlimited hot water from a tap or shower. While the cold-water setup was tolerable for my outdoor spirit, I could not imagine standing unclothed inside a doorless bathroom.

If I were hiking, I could go days without bathing, but here, it was crucial to start our trip by experiencing the Ramnami culture. Hesitantly, I took off my clothes and poured a couple of mugs of water, just as I heard giggles outside. I paused to check if I was imagining things or if it was real. Soon, I saw the shadows of a few kids moving behind the curtain. As I began applying soap, I saw two toddler heads peeking in from the sides of the curtain, giggling again. I panicked, yelled my friend’s name, and hoped she would come to help. She got scared and ran over to see what was wrong. I told her about the curious kids, and she decided to stay at the bathroom entrance until I finished. Later, I returned the favor.

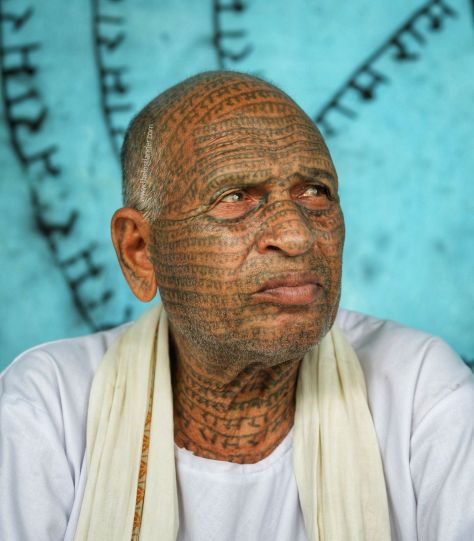

After changing into fresh clothes, my friend and I headed to the porch of their house, where the entire family had been singing hymns of Lord Ram since sunrise, even before we arrived. We greeted them with a coconut and some fresh flowers, which we were asked to bring as part of their tradition of introducing a new guest to the family. Most adults had tattoos reading ‘Ram-Ram’ in Hindi covering their bodies. Some had full-body tattoos, while others had only face, arm, or forehead patches. They all wore pure white clothes handwritten with ‘Ram-Ram’ patterns. Their Dhotis, shawls, and headgear featured the same ‘Ram’ writing in a consistent style. The handmade headgear, unique to the Ramnami, was decorated with peacock feathers. All participants in the Ram bhajan carried strings of small jingling metal bells, each stamped with ‘Ram’ during casting.

We introduced ourselves and joined their Bhajan until lunch was served. I savored a simple Satvik meal made with ingredients from their farm. The faint aroma of firewood used in cooking enhanced the local flavors with a divine touch.

Exploring the daily life of the Ramnamis

We traveled without a fixed schedule, aiming for a slow, immersive experience of this community’s daily life. After lunch, my friend and I joined members singing Ram Bhajans on the porch to understand what defines the Ramnami. We were transported back to the 1890s to learn about their history. Like the rest of India at that time, casteism barred lower castes from entering shared places of worship. Some rebelled by declaring their bodies as temples dedicated to Ram, tattooing the Ram-Nam (Lord’s Name) with a locally made ink derived from herbs. They formed the Ramnami community. A senior member leads events, whether a baby’s birth or a funeral. Their greetings and farewells are solely marked by singing Ram-Bhajans, even during major life events like marriages. They do not conduct any Brahminical rituals, poojas, or havans as part of their practices.

With the rain gods commanding the skies and earth, we saw them prepare their shawls, made from woven, stitched white cloth they crafted themselves. These shawls were then covered with Ram-Nam. After carefully observing them write with their native ink for a while, we joined in to write on some of the other pieces. Once finished, they set them aside to dry, initiating a series of procedures to prevent the white cloth from bleeding black.

When the rains stopped, our host guided us through their village. We crossed a stream, carefully walked along the paddy field edges, and eventually made our way along muddy, winding roads. We met several members of the Ramnami community, mostly relatives or neighbors from the same village. We greeted women working in the fields and enjoyed coffee at welcoming houses. Later, we visited JayaStambh, a small monument commemorating the annual Ramnami mela held here a few years prior. Some older community members joined us there at sunset, singing Ram bhajans as a tribute to the setting sun. Afterwards, we visited a small reservoir across the lake. The Ram Bhajans, sung warmly around a bonfire, echoed over the calm water, with the sky changing colors dramatically until nightfall.

We walked home carefully through the night darkness to avoid slipping on the slush. After a satisfying dinner, we drifted into a peaceful, childlike sleep, concluding a long and exhausting day.

The following morning, we rose early to witness a normal day in the life of the Ramnami. We went to the reservoir with the elder members of our host family, who offered prayers to the sun god and recited blessings before their water dip. After changing into clean clothes, they went back home to continue household tasks such as cleaning, preparing food, and having breakfast.

Conclusion

Spending time at a Ramnami home offered a genuine glimpse into a culture that is remarkably different from the rest of India. The younger Ramnami generation might not be eager to follow the traditional paths laid out by their elders. However, this community exemplifies how faith in God can help us overcome great challenges. They defied the odds, forging their path, which they believe will lead them to a divine connection.

After a simple breakfast and Ram Bhajans, we packed our bags for our next destination in Chhattisgarh. Our host assisted us with pillion rides on two motorbikes, skimming over the slushy village roads before reaching the highway, where we caught a local bus to continue our journey.